- Opening Hours

- Timing: Mon to Sat - 10 AM to 5 PM

- Address: Positron Hospital, Health Center Plot Block B Suncity, Sector 35, Suncity Township-I, Rohtak, Haryana 124001

- Call Us+123-456-78-09

- Opening Hours

- Timing: Mon to Sat - 10 AM to 6 PM

- Address: Positron Hospital, Health Center Plot Block B Suncity, Sector 35, Suncity Township-I, Rohtak, Haryana 124001

Kidney Stone Treatment

Kidney stones form when minerals and salts in urine crystallize into hard deposits inside the kidneys. These can cause intense pain, especially when moving through the urinary tract. Treatment choices depend on the stone’s size, location, composition, and the symptoms experienced. A urologist evaluates each case to recommend the most suitable approach. Small stones may pass naturally with supportive care, while larger or obstructing stones often require medical procedures.

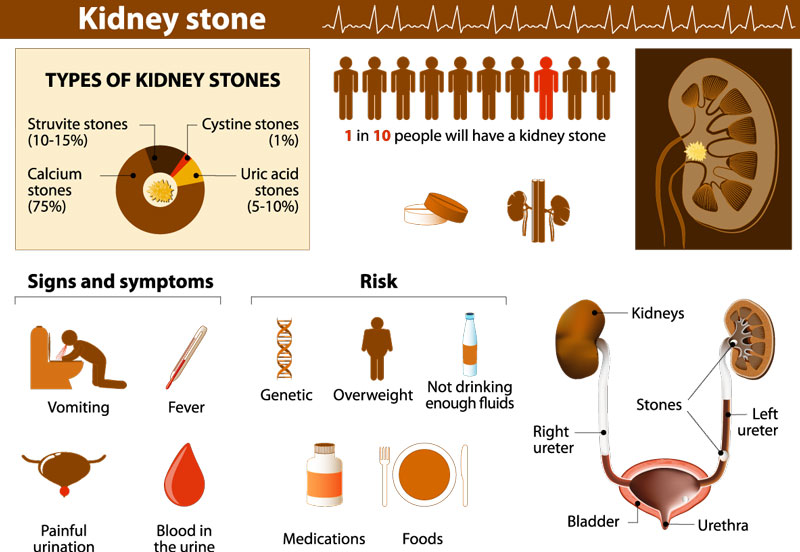

Here are some common types of kidney stones illustrated below:

Conservative and Home Management for Small Stones

Small kidney stones often pass through the urinary tract on their own with increased fluid intake and pain management. Drink plenty of water throughout the day to produce large amounts of clear or pale urine, which helps flush the stone naturally. This process may take several days to weeks, depending on the stone.

For pain relief, doctors prescribe medications to reduce discomfort and inflammation. Alpha blockers relax the muscles in the ureter, making passage easier and less painful.

Supportive home measures include adding fresh lemon juice to water for its natural citric acid content, which helps prevent stone growth and supports dissolution in certain types. Light physical activity, such as walking, encourages stone movement, while applying heat to the lower back or side relaxes muscles and eases cramps.

Follow a diet low in salt and animal protein, while including calcium-rich foods from natural sources. These lifestyle adjustments aid stone passage and help prevent future formation. Always seek medical attention if pain becomes severe, fever develops, or urine shows blood.

Medical and Surgical Treatments for Larger or Problematic Stones

When stones cause blockage, severe pain, infection, or fail to pass naturally, procedures become necessary. Common options include:

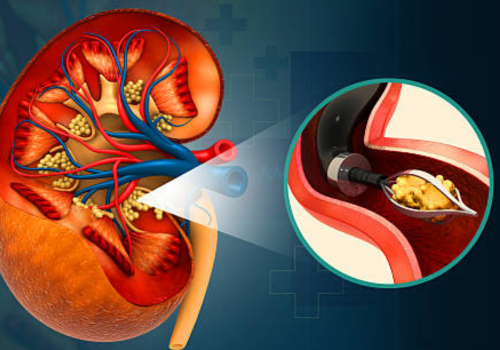

Retrograde Intrarenal Surgery (RIRS) is a modern, minimally invasive procedure used to treat kidney stones without any external cuts. A flexible ureteroscope is gently passed through the natural urinary passage (urethra → bladder → ureter) to reach the kidney. Once there, a laser precisely fragments even large or hard stones into fine dust or small pieces, which are then flushed out or naturally passed in urine.

Ureteroscopy — A thin, flexible scope passes through the urethra and bladder into the ureter or kidney. Lasers or tools break or remove the stone directly. This minimally invasive approach often uses a temporary stent.

- Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy — For very large or complex stones, surgeons create a small opening in the back to access and remove the stone using specialized instruments. This requires general anesthesia and a hospital stay.

Modern advancements include improved lasers, suction-assisted devices, and refined scopes for better precision and fragment clearance. After treatment, analyzing the stone helps tailor prevention strategies, such as specific medications or dietary changes.